A bit of Marlon Brando’s legacy died the day the Supreme Court upheld New Jersey’s right to unilaterally withdraw from the Waterfront Commission. Although much more famous for playing Vito Corleone in The Godfather, his role as Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront was, in my opinion, much more powerful. It brought attention to the plight of dock labourers toiling hard under crooked gang leaders and gave hope that workers may one day unburden themselves from the shackles of a corrupt union. The Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor, pre-dating the movie by one year, was enacted to give that hope and be the means, in part, for their salvation by policing the ports and “eliminating various evils on the waterfront”. Unfortunately, while the Commission did a lot of good, it also failed to stem the racketeering activities of mobsters, union leaders, and businessmen at the port[1] and it wasn’t until the RICO Act, structural changes of port terminal ownership, and a changing economy that racketeering was finally largely eliminated. Now that the Waterfront Commission is gone, will the ports of Newark and Bayonne go back to the conditions of the 1950s? To those found during the FBI’s 1970s UNIRAC investigation? What about the ports of the early 2000s that were menaced by mob characters such as Anthony Ciccone or Andrew Gigante? The answer is an emphatic no. Waterfront racketeering can never come back.

Overview of the Relationship between Union and Industry Racketeering

Before the topic of waterfront racketeering can be fully discussed, it is necessary to establish several important background points. First, it’s important to understand what racketeering means in the context of a port. As explained in Ports, Crime and Security: Governing and Policing Seaports in a Changing World, “the intrinsic complexity of port activities has multiplied the number of existing organizations and has facilitated multiple conflicts to emerge… [which] can decrease rules-based compliance”.[2] If a certain critical mass is reached and institutions start accommodating adverse overlapping between licit and illicit spheres, this can incentivize extra-legal governance and raise security problems. Extra-legal governance and “conflict resolution” is a speciality of La Cosa Nostra and it is no surprise that this group was able to fill this void in the early 20th century to become a potent force on the docks of New York/New Jersey. By acting as a conduit between labour and industry, the Mafia was able to both steal from union coffers and extort money from shipping companies, terminal operators, stevedores, container repair firms, and trucking companies by promising labour peace, contracts and the ability for corrupt owners and executives to make extra money. Overtime, however, the power dynamic changed and that has made the Mafia obsolete and unable to provide “contract enforcement” in the face of a weakening labour movement and the entry of private equity into the industry. Thus, for “waterfront racketeering” to take place, extra-legal governance and contract enforcement must take place. The simple extortion of ILA labourers cannot by itself meet the definition. That is not waterfront racketeering, that’s labour racketeering of a union that just happens to be near a shoreline.

The chaotic birth of the American urban labour movement was a time of violent conflict between labourers seeking better working conditions and industrial capitalists. Amidst this turmoil, racketeers became intermediaries by using their violent skills to control locals to hold down costs for employers.[3] Overtime, they evolved from being strike-breakers to those of extortionists preying on either union members, employers, or oftentimes both. In this manner, they could sell out their members through sweetheart contracts with industry or use the threat of strikes to coherence labour peace payoffs. After World War II, this type of “leg-breaking” racketeering was in large parts supplanted by the extortion and pilfering of union pensions or health and welfare funds.[4] Thus, a Mafia-controlled local can be either used to try and control or extort the industry it represents, or it can be simply used to defraud its union members. A union can be “mobbed up” and not be used to influence or extort industry participants. For instance, the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union (HERE) Local 226 in Las Vegas was clearly influenced by the Mafia and yet it was not an instrumental tool used by the mob to control Nevada’s casino industry.[5] In fact, the Chicago Outfit’s main objective with that union was to fold it into the International, controlled by their alleged associate Edward T. Hanley, to gain access to its Health and Welfare Trust Funds.[6] In an example closer to New York, Colombo mobster Michael Franzese used his influence over the Allied Union of Security Guards and Special Police to loot its Health & Welfare Fund through an insurance kickback scheme rather than extort individual businesses.[7] There was no indication that the union was used as a vehicle for any wider industry extortion. On the other hand, a union was not necessarily required for mobsters to exert tremendous control over industries and their business participants. For instance, Lucchese captain Salvatore “Sal” Avellino was caught on tape multiple times complaining about the lack of help he received from the mobbed-up Teamsters Union Local 813 in his attempt to maintain a cartel over the garbage business on Long Island, New York.[8] Instead of a union, the primary means of controlling the industry came through the Private Sanitation Industry Association of Nassau/Suffolk (PSI), an employer association. While a union can be a powerful tool used by mobsters to infiltrate and dominate industries, it is not a sufficient condition in itself as other factors must be present for it to monopolize or cartelize .[9] The conclusion here is that even if the International Longshoremen’s Association (ILA) is mobbed-up, one cannot jump immediately to the conclusion that waterfront racketeering is taking place.

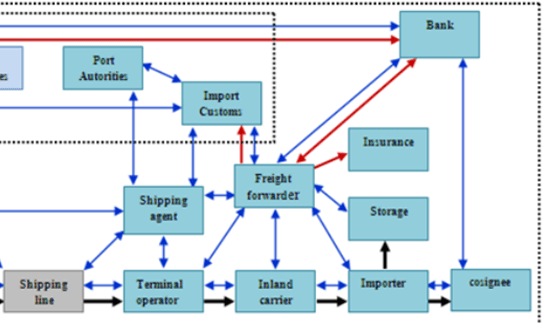

Snapshot of the port value-chain

UNIRAC – The FBI’s Mafia Takedown before “Takedown Day”

UNIRAC was one of the most successful investigative operations conducted by the FBI that helped take down hundreds of unscrupulous businessmen, corrupt union officials, and conniving mobsters. I will keep this section brief because it is ancient history at this point, and I am more interested in looking at the mob’s activities at the dock in the 21st century given its relevance to determining if waterfront racketeering is truly a threat in this day and age.

UNIRAC (short for union racketeering) was an investigation launched by the FBI in 1975 to eradicate La Cosa Nostra’s influence in the maritime industry of America.[10] A four-year investigation resulted in the conviction of 117 people including leading ILA officials, businessmen, and mobsters such as Anthony Scotto, George Barone, and Michael Clemente. The investigation uncovered that the entire port value chain was complicit. Shipping companies like Prudential Lines, Zim American Israeli Shipping Company and Netumar International were either systematically extorted or complicit in kickback schemes with the mob.[11] Furthermore, terminal operators and stevedores were also shaken down such as Nacirema Operating Co., United Terminals, Inc., and Pierside Terminal Operators Inc. with their owners being complicit in the schemes to enrich themselves.[12] Using this control and participation from corrupt businessmen, the mob was also able to extort secondary service providers such as container repair firms and trucking firms operating at the piers. Worse, the Port Authority itself was compromised due to its close relationship with Gambino captain Anthony Scotto which enabled the corruption of the entire port ecosystem. UNIRAC’s investigations showed that the mob functioned as a conduit between management and labour, extracting payoffs for peace. It also demonstrated that businessmen were more than happy to cooperate with the Mafia as it enabled them to win new contracts and gain a competitive edge over their peers. Thus, by being in the nexus between both management-labour and corporate-corporate relationships, the Mafia was able to provide “extra-legal” governance at the port by creating and enforcing contracts between the various participants. It provided “order” to a chaotic environment. Although a prosecutorial success, UNIRAC ultimately failed to stem corruption at the ports of New York/New Jersey and as such, waterfront racketeering persisted into the new century.

Waterfront Racketeering in the 2000s

The new millennium brought new headlines about ongoing corruption on the docks of the East Coast. Despite the success of UNIRAC in the 1970s/1980s and the civil RICO trusteeship cases against the New York/New Jersey locals in the 1990s, racketeer influence on the docks seemed to be as pervasive as ever. Sensationalist headlines made it seem like businessmen and dock workers alike couldn’t breathe without the express permission of Vincent Gigante or Peter Gotti, much less conduct their business in a fair manner. What was reality actually like on the waterfront in the early 2000s? Did the scope and scale of organized crime’s control match that of the UNIRAC days or was there meaningful progress? To tackle this, the Gambino and Genovese cases must be examined separately.

Following John J. Gotti’s (Sr.) and John A. Gotti’s (Jr.) convictions on various racketeering charges in the early and late 1990s, respectively, Peter A. Gotti took the helm as the new leader of the Gambino crime family. First serving as an Acting Boss, Peter became the official don either shortly before or upon his brother’s death. His reign would be short-lived as the government filed a massive 91-page racketeering indictment against him and members and associates of his family.[13] Two sets of charges stood out. The first, and the one that got the most media traction, was the Gambino’s attempted extortion of past-his-prime Hollywood “star” Steven Segal.[14] The other set of charges were sensationally summarized in articles such as the one written by Jim Callaghan and Tom Robbins in The Village Voice ascribing the Gambino family “with continued control over much of the city’s waterfront.”[15] The predicate RICO acts concerning the docks can be broken down into six broad sections: 1) Control over ILA Local 1814, 2) Control over ILA Local 1, 3) Control over the Management – International Longshoremen’s Association Managed Health Care Trust Fund (MILA), 4) Extortion of the Howland Hook Container Terminal, 5) Extortion of a waterfront trucking company, and 6) Control over job allocations and extortion of individual waterfront employees.[16] I will tackle the first three sections in the Genovese focused portion because it relates to their schemes. The last point does not need to be addressed because the extortion of any one individual cannot constitute “waterfront racketeering” in its truest sense as the Mafia is not providing contract enforcement or “extra-legal governance” between conflicting actors in a port setting. Thus, I will discuss in more detail points 4 and 5 as they show, more than even the Genovese indictments, clear indications of “conventional” waterfront racketeering reminiscent to that of the UNIRAC days and highlight the “facilitation services” of the Mafia.

Surveillance Photo of Peter Gotti and Anthony Ciccone

Carmine Ragucci was a politician and a businessman, often a lethal combination that afforded one great influence. Plugged into borough and state politics, Ragucci enjoyed many friends in high places, in no small part due to his ability to contribute generously to political campaigns. In 2001, he became the chairman of the Staten Island’s Conservative Party aided by ally and borough president James Molinaro.[17] One of the sources of Ragucci’s financial capital came from his part-ownership and position as CEO of the Howland Hook Container Terminal Inc. which operated out of the Howland Hook Marine Terminal on Staten Island, New York (GCT New York).[18] Ragucci had long-ties with that particular marine terminal, as he was a former manager of it before it was shuttered in the early 1990s.[19] The terminal began operating again in 1996 and starting in 1997, Ragucci began to payoff Gambino Captain and former ILA Local 1814 official, Anthony “Sonny” Ciccone, for “labour peace”.[20] What’s interesting is that neither the indictment, the appeals, or the testimony featured in newspapers indicated that Ciccone or any other member of the Gambino’s “asked” Ragucci to pay tribute to avoid labour problems. It was simply ingrained into the mentality of companies operating in the port setting and a testament to the mob’s continuing implicit role as an arbitrator of disputes and facilitator of transactions/services. The government’s theory was that payments from Ragucci were intended to solidify Ciccone’s influence over ILA Local 1814.[21] That local represented unionized maintenance workers and longshoremen at Howland Hook Container Terminal and Red Hook Marine Terminal in Brooklyn. ILA Local 1 represented checkers of containers at both terminals.

Anthony Ciccone began accepting these payments through Frank “Red” Scollo, then president of ILA Local 1814 and ordered the official to comply with Ragucci’s wishes regarding labour issues at the terminal.[22] Scollo delivered the tribute to either Ciccone or Gambino soldiers Anthony Pimpinella and Primo Cassarino and Ciccone would get upset when they were not paid on time reminding Scollo to tell Ragucci, “to do the right thing”.[23] Payments were usually done on a quarterly basis and sometimes the envelopes contained as much as $9,200. In total, the payoffs lasted between 1997 and June/July of 2001. Assuming payments started at the beginning of 1997 and taking the maximum reported payment as the average, a total of $165,600 (~$313,000 in today’s money) was paid over 18 quarters. This is a paltry sum considering that well-run container terminals can yield EBITDA margins of ~20-40%. The Gambino’s extortion of Howland Hook Container Terminal ended after Ragucci left his position with the company, supposedly due to disagreements with his (non-mob) partners.[24] This terminal is now run as ‘GCT New York’ and owned by the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (OTPP), IFM Investors (IFM), and British Columbia Investment Management Corporation (BCI), sophisticated infrastructure private equity investors. OTPP acquired the terminal alongside GCT Bayonne from Ragucci’s old Asian partners for $2.4 billion in 2006. The company generated $444.3 million in revenue and $99.8 million in EBITDA according to CapitalIQ… But I’m getting ahead of myself.

The second main business Anthony Ciccone was accused of extorting was Bridgeside Draydage, a trucking company owned by Frank Molfetta.[25] Molfetta entered into a contract with Carmine Ragucci in 1994 and 1995 that would result in Bridgeside becoming the exclusive broker-dispatch at the Howland Hook Marine Terminal.[26] In return, Molfetta would pay Ragucci an initial sum of $150,000 and $100,000 later. In 1994, Ragucci received his $150,000 but went back on the agreement in 1996 after he allowed another trucking firm to encroach on Molfetta’s turf.[27] While Bridgeside Draydage continued to perform trucking services at the terminal, Molfetta refused to pay the additional sum given the breach of contract and because he did not even recoup his initial $150,000 “investment”. Fast-forward to late 1999 or 2000, Ragucci informed Frank that Anthony Ciccone wanted to see him. At the initial meeting between the two men, Molfetta described the terms of the contract to the Gambino captain with the latter instructing the former to not pay the initially agreed-upon contractual sum. Instead, at a second meeting, Molfetta agreed to pay Ciccone $1,500 per month (after haggling down from a $2,500 monthly payment). During grand jury proceedings and later at trial, Molfetta offered two motivations for the payment. Testifying before the grand jury, Molfetta explained that he paid Ciccone out of fear due to the power that men like him wielded. At trial, however, Molfetta stated that he offered monthly tribute to Ciccone because the latter got him out of the contract with Ragucci. Molfetta was later indicted for perjury.[28] Regardless of the exact reason, this example is yet another clear demonstration of the Mafia’s continued role of being able to provide “extra-legal” governance at the port whereby Ciccone was able to intervene in a dispute between two port actors and resolve their issue. The Anthony Ciccone trial demonstrated that even in the year 2000, the mob was able to function at a “high level” at the docks and indeed still conduct “waterfront racketeering” in its truest sense. However, the hyperbolic assertions of Jim Callaghan and Tom Robbins and other journalists at the time were indeed hyperbolic. The “control” this indictment proved was a marketable step down from the influence the mob displayed during the days of UNIRAC. The government did not contend that any shipping lines were extorted. Furthermore, as soon as Ragucci was booted from his post, the Gambino family and the ILA were unable to continue their extortion schemes. Finally, the Gambino’s short-lived dominion over Staten Island’s terminal did not afford them control over much of the city’s waterfront given the fact that by this time New Jersey handled much of the container volume entering New York’s harbor. At the end of the day, simply fewer players were extorted along the port value chain which crystallised the waning influence of the mob over the docks with the passage of time. The Genovese indictment highlighted even less waterfront racketeering!

Antony “Sonny” Ciccone

In January 2002, the government announced another massive indictment targeting the Genovese crime family. Among the catches were imprisoned Boss, Vincent Gigante, Acting Boss Ernest Muscarella, former Acting Boss Liborio “Barney” Bellomo, Andrew Gigante, and several others.[29] Its waterfront charges boiled down to rigging elections to control high-ranking ILA officials and rigging contracts to service various ILA-affiliated funds.[30] In of itself, neither of the two can be considered “waterfront racketeering” and are simply examples of “generic” union racketeering that happened to a union that represented port workers. Through pre-trial motions and subsequent government filings, however, more information came out regarding the Mafia’s extra-legal governance services. I will now tackle both the ILA-fund frauds and extortion of port businesses separately.

The Genovese collaborated with the Gambino’s to rig the MILA Pharmacy Benefits Manager (PBM) contract to award it to their associates in exchange for a kickback. In May 1997, MILA narrowed down two candidates, Express Scripts and GPP/VIP to administer their prescription drug plan for its members. Express Scripts was a large, professional, and experienced company, one that was preferred by both the fund’s actuarial consultants and management trustees.[31] GPP/VIP was a start-up run by Dr Vincent Nasso, an associate of Anthony “Sonny” Ciccone, and Joel Grodman. For a $400,000 payment, Ciccone agreed to help Nasso secure the contract. Sonny utilized the help of Genovese members Larry Ricci and George Barone to help “lean on” alleged Genovese associate Harold Daggett to support the GPP/VIP bid in exchange for $75,000. In a compromise solution, MILA awarded the mobbed-up company a contract to administer the plan for the North Atlantic ports from Massachusetts to Virginia, while Express Scripts was awarded a contract to oversee the South Atlantic ports from North Carolina to the Mexican border. However, despite Express Scripts receiving better reviews, its contract was terminated on January 1st, 2000, and GPP/VIP now serviced the entire East Coast. In the summer of 2001, the company requested to raise prices and as a result, MILA sent out an RFP (request-for-proposal) soliciting new bids for the contract. Ciccone didn’t want to give up the lucrative venture and again tried to rig the tender process. This time it was to no avail. GPP/VIP was going up against Advance PCS, the largest private PBM in America, and MILA would save $4 million over a three-year period using the latter over the former. MILA’s trusteeship was split as to the selection of their next vendor. GPP/VIP’s contract was extended until the summer of 2002, but after an arbitration process, Advance PCS became the sole PBM provider for MILA. The mob’s influence can only do so much…

Similar conspiracies were enacted to control the MILA Mental Health Benefits Contract (MHBC) as well as various Metro-ILA fund services including fund investment advisory, PBM and MHBC contracts as well as the ILA Local 1922’s MHBC contract.[32] For instance, the MILA MHBC contract was rigged in favour of Compsych, which paid James Cashin $5,000 per month as a “consultant”, despite some actuaries proclaiming their bid expensive and non-competitive. James Cashin was an associate of the Genovese family, and after George Barone’s consent, ILA trustees such as Daggett were “particularly vocal” about its approval and contract extension. Compsych was similarly awarded Local 1922’s contract after Barone directed ILA official Arthur Coffey to give it to them. Finally, Compsych was also given the Metro-ILA MHBC contract after “a push” from Daggett. Metro-ILA also awarded GPP/VIP its PBM contract in the summer of 1998 at the direction of Daggett, who allegedly knew, of its relationship with organized crime. Liborio Bellomo, Peter Tarangelo, and Thomas Cafaro also conspired to get Metro-ILA’s fund advisory contract in 1995-1996, but this particular scheme fell apart after Barney’s arrest in June 1996. Regardless of success or failure, these schemes constitute union fund racketeering, but these contracts will become important shortly to compare and contrast the Mafia’s influence on the union in the present day.

George Barone

Far more interesting were the details surfacing around the Genovese’s relationship with the Metropolitan Marine Maintenance Contractors’ Association (MMMCA or Metro) and Andrew Gigante’s waterfront activities. Containerization radically altered port activity and fundamentally changed the Mafia’s approach to waterfront racketeering from the On the Waterfront days. George Barone, the Genovese’s eyes and ears on the docks of New York and then Florida, apparently had the foresight to understand the future value chain at port terminals and realized the ancillary services containers would require.[33] To capitalize on this development, he helped negotiate favourable and profitable union contracts with large corporations that leased and repaired containers and placed his underworld associates in key labour and management positions. All told there were millions of dollars in opportunities for the Mafia and vendors that “played ball”. To control the corporate side of this arrangement and serve as a conduit between industry, vendors, and labour, the Genovese and their Gambino allies used Metro, an association that included two dozen businesses repairing containers and providers of other needed services to maintain a functioning port ecosystem.[34] The government maintains that this organization was used to strengthen the mob’s grip over the ILA, but it functioned as much more than just that. It was another tool in the Mafia’s “toolkit” to be able to provide extra-legal governance and order at the port. After all, if it can control both the corporate and labour side, it can execute its contract enforcement role and provide “value” to all players.

Andrew Gigante

When googling the Metro today, the first name on the ‘Member Contractors’ tab is A.G. Ship Maintenance Corp. The firm was founded by Albert Guido and by the 1970s, his son Bert, had a near monopoly on New York/New Jersey’s container repair business.[35] Bert also led the MMMCA and in 1990 got into trouble as a trustee of the Metro-ILA benefits fund which forced him to relinquish control of his companies to Christopher Guido. Police described Bert as an alleged associate of the Genovese crime family and on his payroll, one could find the name ‘Andrew Gigante’. Gigante worked at the port since the mid-70s and was the owner of two firms, Portwide Cargo and Bay Container, from which he drew an annual salary of $350,000.[36] According to the government, the younger Gigante also secretly controlled Guido’s company. At one point, Guido handed over a $50,000 extortion payment to his mob benefactors, signifying their influence over his firm. At other times, Guido would funnel extortion payments through Local 1804-1 officials.[37] Another Genovese plant at Metro was soldier, Pasquale “Patty” Falcetti, a vice president with the organization in charge of negotiating contracts between the association and ILA Locals 1804-1 and 1814, further facilitating contract enforcement. Gigante sought to use George Barone’s influence on the Miami waterfront to win a big container-repair contract for Guido’s firm, but this situation spiralled into a conflict between the mobsters. Instead, Barone’s Miami ILA local pulled a slow down on Guido and Gigante’s company.[38] George was later arrested, flipped, and blew the cover on the Genovese’s control over the East Coast’s waterfront. With the unsealing of the indictments, prosecutors proclaimed that the Genovese family won “extortionate control of the New York, New Jersey, and Miami piers”.[39]

As with the Peter Gotti/Anthony Ciccone indictment, this statement proved to be somewhat hyperbolic. The meat and potatoes of charges dealt with the Genovese’s control of the ILA and their various schemes to defraud its membership. From all the information that came out it’s hard to quantify the Genovese’s control over Metro and its individual members to determine the degree of influence that they had. Gigante’s attempted use of an ILA local to help win a contract suggests that some of the ‘extra-legal’ governance the mob provided still existed in its ability to affect business and commerce at the port. But we also get clues as to the limitation of the influence exerted by the Genovese family. The biggest evidence for that comes from the fact that management-appointed trustees at the Metro-ILA fund seemed to always resist “mobbed-up” vendors proposed by union-appointed trustees. This disagreement, for instance, is what led GPP/VIP to lose their contract in the arbitration with Advance PCS.[40] Logically speaking, if the mob truly controlled employers and their corporations, this wouldn’t have taken place. Thus, at best, their influence was piecemeal and limited to certain companies that did not allow for monopolistic or even cartel-like control of the docks. When taken together, the Anthony Ciccone and Liborio Bellomo cases, the so-called ‘Waterfront Enterprise’ proved to be a remarkable step-down when compared to UNIRAC.[41] The mob was moving away from the core components of the port ecosystem and forced to migrate down the value-chain and extort more and more periphery service providers in the network. Things at the port settled down for a while and the next update wouldn’t come until the following decade.

Waterfront Racketeering in the 2010s

A new decade brought with it new racketeering indictments alleging that the docks of New Jersey and New York were still under the thumb of organized crime. On January 20th, 2011, the FBI arrested some 127 Mafiosi and their associates up and down the East Coast in what was dubbed as “Mafia Takedown Day”.[42] Buried in the FBI’s press release was the following quote: “In the union case involving the ILA, court documents allege that the Genovese family has engaged in a multi-decade conspiracy to influence and control the unions and businesses on the New York-area piers”.[43] The relevant indictment centred on Genovese soldier Stephen “Beach” Depiro, the latest mob-appointed overseer at the port working on behalf of familiar characters like Tino Fiumara and Mike Coppola.[44] The indictment charged that the Genovese family dominated ILA Locals 1, 1235 and 1478 from about December 1982 up until January 2011 and through the use of actual and perceived violence, extorted longshoremen and dockworkers into paying tribute around Christmas time (Christmases) from the labourer’s “container royalty fund” checks. In addition, the Mafia was able to control hiring at the docks and deprived union members of their rights to a free and democratic institution that served their best interests. Alongside Depiro, a slew of ILA officials and representatives were indicted including the president of Local 1235, the vice president of Local 1478, a Local 1 checker, and several delegates, foremen and stewards. Now these charges certainly proved control over the unions on the New York-area piers, but they don’t prove control over waterfront businesses. Two corporations were mentioned in the indictment and detention memorandums, Maher Terminals in Newark and Port Newark Container Terminal (PNCT). Concurrently to the indictment that charged Depiro and his ILA associates, a separate indictment was unsealed against Patrick Cicalese, Chief Planning Clerk at Maher, Robert Moreno, ILA Local 1478 shop steward, and Manuel Salgado, a “Gang Boss” for PNCT, for obstruction of justice relating to their contact with Depiro. As it turned out, both Cicalese and Salgado, were under Depiro’s influence and Salgado was explicitly described as having conversations with others about making mob payments around Christmas time. However, it is clear from their perjury indictment that any talk of payments was regarding other union members, not the corporations they represented.[45] Therefore, the conclusion of this case inconclusively backed the government’s original assertion in its press release. The unions were still infested, but it seems the Mafia’s influence was very much dampened, and it was relegated to victimizing dock workers. There was no indication of the Mafia providing ‘extra-legal’ governance on the port, no suggestion that employers of any sort themselves were extorted. If anything, this case showed that there was no ‘waterfront racketeering’ at the piers of New York and New Jersey.

Stephen Depiro

Around the same time, Stephen Depiro’s superior, Michael Coppola was having a bad time in the neighbouring Eastern District of New York.[46] He was awaiting trial for a racketeering case that alleged his participation in the murder of fellow Genovese member Johny “Coca Cola” Lardiere and his extortionate activities at the waterfront. The racketeering activities were more limited in scope but ranged over a longer period of time. Coppola was charged with dominating the affairs of ILA Local 1235 between January 1974 and March 2007 and using it as a vehicle to extort monthly and Christmas tribute from union members and businesses alike. That piqued my attention as it could demonstrate continued mob-provided ‘extra-legal’ governance should the extortion of waterfront businesses extend well into the late 2000s. Alas, that was not the case. The government’s prime witnesses such as George Barone or Michael “Cookie” D’Urso recounted ancient history during the trial, telling the jury stories of mob dominance during the heyday of the Mafia. In fact, examples of corporate extortion were the ones from the UNIRAC days, such as stevedore Quinn Marine paying Christmas tribute or Fiumara’s tax on Robert Delaney’s undercover trucking firm. The most recent instance of business extortion was D’Urso’s recorded conversation with Thoms Cafaro regarding Barone’s demand for a $90,000-$100,000 “Christmas” payment from Andrew Gigante. That doesn’t count for obvious reasons. Instead, the trial showed that the Genovese’s influence in the present day only extended over the port union which enabled them to extort ILA members and control hiring practices. The freshest evidence pointed to this conclusion which overlapped with the facts presented in the Depiro case. Once again, the statement that mob racketeering on the waterfront was alive and well proved to be premature. This brings me to the final and as far as I am aware, the latest case involving the Mafia, the ILA, and alleged nefarious activities at the ports of New York/New Jersey.

When I first read about this case in Ports, Crime and Security I couldn’t believe I didn’t hear about it before. Cases against the ILA involving the extortion of their own members are one thing, but this lawsuit alleged Mafia power on an almost UNIRAC level. Unfortunately, any excitement died down rather quickly once I started reading about the background situation and putting everything into context.

American Stevedoring Inc. (ASI) was founded and run by Sabato “Sal” Catucci, a port executive with deep political connections in the Brooklyn community. Different sources differ, but ASI became the operator of Red Hook Container Terminal in either 1992, 1993 or 1994.[47] The once mighty Brooklyn waterfront was in a decrepit shape in the 1990s as containerization, access to railway logistics and Port Authority (PA) attention made the Port Newark – Elizabeth Marine Terminal the premier gateway for goods entering the East Coast of the US.[48] Thus, Catucci and ASI kept the dream of a “viable Brooklyn waterfront” alive, operating its only container terminal throughout the 1990s and well into the 2000s. But beneath this façade, it was well understood that Brooklyn’s role as a centre of commerce was long gone and that any grandiose illusions were just that, illusions. Operating Red Hook was an uneconomical decision for the Port Authority as they spent over $5 million per year subsidizing the terminal.[49] Other sources say the cost could have been as high as $25 million.[50] In total, Red Hook and Brooklyn Marine Terminal together cost the PA $518 million from 1991 to 2016.[51] As anyone who has followed Brooklyn’s real estate prices, the borough’s land has gotten very expensive, and the waterfront was a prime target for redevelopment to reinvigorate decades of urban decay. Well, Red Hook and adjacent city-owned properties could fetch upwards of $2.7 billion if rezoned for luxury housing, condominiums, and other uses. In fact, former New York mayor Michael Bloomberg long coveted the space and in 2002 planned to take over the port for “development czar” Charles Gargano to transform it into hotels, beer gardens, and other complexes.[52] Catucci had to enlist the help of his own political muscle in the form of Congressmen Jerrold Nadler and city council member David Yassky to fend off Bloomberg’s ambitions and protect the few hundred remaining good blue-collar jobs still left in Brooklyn.[53] After a contentious battle and a “will they, won’t they” type drama, ASI’s lease was renewed with the PA for another 10 years in 2008.[54] Catucci promised to pay $41 million in rent over the life of the lease and an additional $29 million to operate the container cranes in exchange for $5.6 million in subsidies. Despite the renewed lease, tensions between ASI and the port flared soon thereafter.

In 2013, Sabato Catucci filed a bombshell civil RICO lawsuit against the ILA, ILA president Harold Daggett, the NYSA-ILA Pension Fund, the Port Police Union, and a host of other union officials and businessmen alleging the group (‘the Waterfront Group’) of committing racketeering offences against American Stevedoring to drive it out of business.[55] ASI accused ILA president Daggett of threatening and strong-arming Catucci to either comply with their illegal activities or relinquish control of the container terminal to a company more amendable to the Waterfront Group. Criminal rackets such as phoney workers’ compensation insurance schemes, no-show/low-show jobs, gambling, and loansharking were replete on the docks of Brooklyn and were all run with approval from mob-linked ILA and business executives. Any resistance from Catucci was allegedly met with stern warnings about his standing with the Mafia and ILA Local 1814 secretary-treasurer Louis Pernice threatened to take him out of the terminal “in a box”.[56] The Waterfront Group wanted Catucci to comply and participate in these joint-criminal activities, but he supposedly refused them at every turn. After years of resisting the mob, things came to a head in August of 2011.

By 2011, Catucci’s company was supposedly in dire financial straits. ASI was owned $241,506 in demurrage fees by Phoenix Beverage Co. owned by father-son duo Gregory and Rodney Brayman.[57] MTC Trucking acted as the “house trucker” for Phoenix and it was owned by defendant Michael Farrino and Daggett “forced” ASI to drop its attempt at collecting those fees. Further adding to Catucci’s woes was that the Port Authority and Daggett joined into a “conspiracy” to put further pressure on ASI by no longer subsiding its barge handling facility. Finally, as a result of ASI withdrawing from the ILA and PPGU pension benefit funds, Daggett and other union officials ordered a port-wide strike to shut down Catucci’s operation on September 23rd, 2011. With no resolution in sight, Sal Catucci was “forced” to sign a succession agreement just three days later and on September 27th, 2011, to allow Red Hook Container Terminal LLC (RHCT) to take over operations at the port. The Mafia and corrupt labour won. Catucci became just another name on a long list of proud entrepreneurs of Italian heritage that fell victim to the evilness of the mob.

Sal Catucci

If the allegations were proven to be correct, then this would be an extraordinary showcase of the continued influence of the Mafia and its staying power on the docks of New York and New Jersey. Not only were they able to arbitrate disputes between different waterfront businesses, but they were also able to have a say in the running of the terminal itself. Such power over a container port, however small, would overshadow Ciccone’s “control” over Howland Hook and harken back to the days of UNIRAC. Fortunately for us, Catucci seems to be an eccentric individual who might have embellished a thing or two. First, it’s important to examine what were Catucci’s actual mob connections and examine in full the circumstance of his departure and the aftermath of his eviction from Brooklyn’s waterfront.

Allegations of Catucci’s association with the Mafia largely stem from statements made by Assistant District Attorney Paul Weinstein during tax evasion proceedings against Joseph Perez in 2004.[58] Perez was a director of sales and operations for American Maritime Services (AMS), a large ship cleaning firm that was a member of MMMCA/Metro. During his time with the firm, the Waterfront Commission stated that he hired questionable employees including Genovese associate Robert Santoro who was allegedly around Genoese captain Salvatore “Sammy Meatballs” Aparo. As part of Perez’s trouble with the law, assertions came out in court that Joseph Perez, Ronald Catucci (treasurer at AMS), and his brother Sal Catucci (ASI) all participated in a scheme to divide control of the docks between the Genovese and Gambino crime families. Specifically, Weinstein told a judge that they had evidence that Ronald and Sal Catucci were, “Gambino associates who do business primarily out of Brooklyn”.[59] While neither Sal’s or Ronald’s connection with organized crime was proven in court, it is logical to assume they had contact with mobsters considering their long history on the docks and the fact that as a “small business”, ASI would be a prime target for extortion. Finally, we must examine the real reason for Sal Catucci’s untimely exit from Red Hook Terminal and why the Mafia probably had nothing to do with it.

As mentioned previously, Red Hook’s viability as a container terminal was a highly contentious matter during Michael Bloomberg’s administration and as a result, the Port Authority only renewed ASI’s lease in exchange for some steep terms.[60] ASI started its new lease already $2.6 million in arrears and apparently didn’t pay any rent during its last few years at the port. As a result, it was likely simply evicted from the terminal for non-compliance with its agreement. Furthermore, Catucci’s lawsuit mentions a “port-wide strike” whereas contemporary newspapers characterized the action as an impromptu protest. If there was an official strike action or anything of that magnitude that threatened to shut down the port’s operation, it would have been reported as such. Finally, the Waterfront Group’s “preferred” operator RHCT was not even guaranteed to run the terminal after ASI’s departure. French shipping giant CMA CGM temporarily took over as the stevedore for the port and there were rumors that the Mediterranean Shipping Company (MSC) was in contention to take over. The Port Authority and ASI settled in 2014 for $25 million, with all of it being used to either cover unpaid rent or other outstanding debt.[61] The Manhattan District Attorney’s Office even investigated the deal, but nothing seems to have come out of it. And this is the crux of it. If something truly shady was going on and with how vocal Sal Catucci was regarding Mafia activity on the docks of Brooklyn, the government would have surely investigated it and produced indictments. With hindsight, Catucci’s lawsuit seems to have been nothing but one last attempt at a cash grab now that his trucking company “racket” at Red Hook was gone with ASI’s exit from the terminal operating business.[62]

The Kings of Capital

Immortalized in a book and a movie sharing the same name, Barbarians at the Gate, the acquisition of RJR Nabisco by Henry Kravis and George R. Roberts (KKR) marked the coming-of-age of the leveraged buyout (LBO) as a distinct asset class within capital markets. Since then, private equity’s importance in Corporate America has grown exponentially and today global dry powder (committed but uninvested capital) sits at almost USD$2 trillion dollars.[63] Although initially focused on corporate buyouts, private equity shops have morphed into asset gatherers and as a result have outgrown their initial mission. These days, most private equity shops (think Blackstone, Apollo, KKR, etc.) manage dozens of strategies and the bulk of their AUM (assets under management) sits in real estate or credit strategies. It is precisely the entry of private equity and the corporatization of ports around the world that has changed the power structure at the docks which has resulted in the diminishing need for the Mafia’s extra-legal governance services.

Infrastructure as a modern asset class was born in Australia during the late 1990s and early 2000s with the key privatizations of certain airports. The value proposition for investors was simple, infrastructure assets provided GDP/inflation-linked revenue growth with considerable downside protection due to their essential nature and monopoly-like characteristics. For cash-strapped governments, privatization of public assets was an easy and quick way to monetize dormant assets to plug gaps in growing budget deficits and punt maintenance and capital expenditure obligations to the private sector. A “win-win” situation. Early on, both Australian public asset managers (think IFM and the Queensland Investment Corporation) and private general partners (think Macquarie Group and Babcock & Brown Infrastructure Group) thrived and were the key infrastructure investors around the world. Playing a secondary role were large insurance companies like AIG and banks like Deutsche that held these investments on their balance sheets. During the 2008 financial crisis, many large infrastructure investors got into trouble due to high fund leverage and as a result, Australian firms were superseded by large North America-based investors. For instance, Canadian giant Brookfield got its big break in infrastructure after purchasing a substantial portion of Babcock & Brown’s assets during its period of distress in 2008-2009. After the Great Financial Crisis, fund managers like Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP) and Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners came to dominate the field with Canadian pension funds and classic private equity GPs in tow.

In the early 2000s, terminal ports and stevedoring firms were orphaned assets, not prioritized or really cared for by the insurance firms or banks that owned them. For instance, Ports of America provides a quintessential example of the journey these assets went through before ending up in the hands of private (public) equity. DP World, a UAE-based port investor acquired P&O Navigation, a British shipping and logistics company in 2006. However, as investors know, things can become politically tricky when a Gulf-backed investor (like ADIA) tries to invest in a strategic infrastructure asset. The U.S. was sensitive to this transaction and as a result, AIG’s Highstar Capital acquired P&O’s core North American assets that would form the nucleus of Ports America Inc. AIG was famously rocked by the Great Financial Crisis and eventually Highstar sold Ports America to Oaktree Capital in 2014. Ports of America is now owned by CPP Investments, a Canadian-based pension fund. Today, 3/5 of New York-New Jersey’s container terminal operators are owned by private capital.

Unlike small business owners or neglected assets operating with little oversight from upper management, private equity is not susceptible to systematic extortion. Container terminal operators these days are vertically integrated businesses that are their own stevedores in most cases. Due to the high demand for their services (especially at gateway ports like NY/NJ), they have captive customers and secondary service providers. As such, contract enforcement services became less and less of an issue negating the need for the Mafia. Furthermore, these are multi-billion-dollar organizations with armies of lawyers and investors, the political connections, and the IQ necessary to operate businesses without the need for the Mafia’s services. Investment banks serve as key relationship intermediates in connection to large financial transactions. Simply put, the power imbalance is just not there anymore. Former Lucchese Acting Boss Alphonse “Al” D’Arco’s failed attempt to shake down cosmetics giant Estee Lauder is a classic example of the mob’s inability to extort large corporations.[64] As former UFC champion Daniel Cormier once said, “There are levels to this game”. Above all, however, private equity is the quintessential steward of Milton Friedman’s ethos and association with the Mafia would be bad for long-term profits due to the reputational damage they would suffer. While investors acknowledge that there are shady characters employed at the docks, personally I have not seen the Mafia come up as a key risk or an item to be concerned about during due diligence. Patsy Parisi said it best on The Sopranos when he tried to extort “Starbucks” by saying it’s over for the little guy.

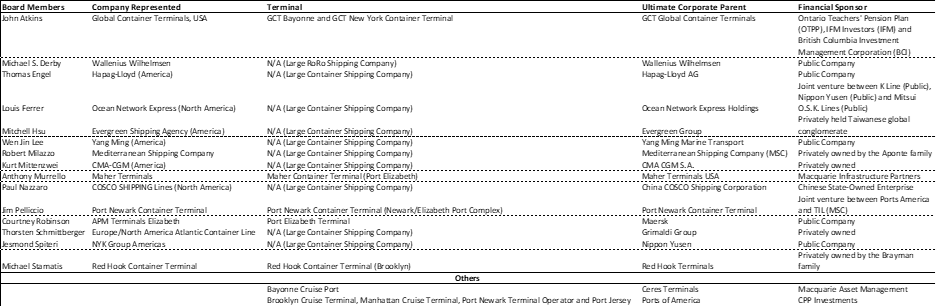

Further evidence of the corporatization of the docks can be seen in the composition of the board members representatives of the New York Shipping Association. A summary can be seen below:

Without exception, all board members represent companies that are owned by private equity, large publicly traded companies, state-owned corporations, or wealthy families. The only real weak link on this list is the aforementioned Red Hook Container Terminal LLC owned by the Brayman family.[65] Two mitigants, however, exist that make mob involvement with them seem unlikely. First, the Brayman family’s primary source of wealth is their ownership of Phoenix Beverages, a publicly traded company that is one of the largest beer distributors in America. Alcohol manufacturers and large-scale distributors are highly regulated, and it seems unlikely that the family would risk their crown jewel for some port extortion with the Mafia. Second, the ILA local in charge of Red Hook is Local 1814. While historically it was the largest local on the East Coast and the crown jewel of the Gambino family, membership declined by over 40% between 2002 and 2019. A failing local would mean a weakening power base (and that’s assuming it’s still mobbed up) and a declining ability to provide “labour peace” and contract enforcement services. Regardless, Brooklyn is simply meaningless in the context of the NY/NJ waterfront, handling just 100,000 containers per year versus New Jersey’s six million.[66]

Another factor in the unlikeliness of the Mafia exhibiting any real influence over the docks of the Tri-State area has to do with the weakening of the labour movement, both real and perceived. Below is a summary of ILA locals that have played a role on the waterfront and have a history of mob infiltration:

As one can plainly see, since the start of the 21st century, overall, ILA membership declined by approximately 6%. The hardest hit locals have been the ones located in Manhattan and Brooklyn and overall New York membership is down ~37%. On the other hand, New Jersey membership has grown since 2002. A couple of conclusions can be drawn from this chart. The first is that the Gambino locals have been the hardest hit with the Genovese’s Manhattan locals not doing too well either. This is largely a reflection of the local economy. While cruise terminals have stemmed some of the pain in Manhattan, the slow conversion of the Brooklyn waterfront into condominiums and parks has led to the decline of dock activity in that region. While the Genovese (if they still have control) locals have gained overall membership, their ability to exert leverage has theoretically diminished since the early 2000s since they must deal with the most corporatized terminal operators. Furthermore, there’s almost no economic gain to be had. Between nine locals, the combined assets add up to just under $50 million, a paltry sum in today’s economy. As the adage goes, great risk requires great reward, and these figures just don’t justify the racketeering sentences mobsters would get from trying to loot them. That’s of course unless the “Ivy League” has stooped down to the desperation level of the Colombo’s.

With the current political climate, the threat of a labour strike is more imagined than real in America, especially for something so vital to the economy and logistics as container ports. While in the past the Mafia could threaten business owners with slowdowns and work stoppages to extort “labour peace” payoffs or use it to win or perform dispute resolution on contracts, these days it’s just not really feasible. A recent example of this was the railroad strike this past December. Despite a labour “friendly” party at the helm, President Joe Biden signed a bill to block a U.S. railroad strike by workers from four locals who rejected their tentative contracts due to lack of paid sick days.[67] And it’s not just this administration, the government has been extremely sensitive about strikes disrupting major transportation nodes since President Ronald Reagan’s Air Traffic Control debacle in 1981. Ports on the West Coast of America seem to be in a striking mood, but it remains to be seen how effective it really is and if/when the federal government intervenes.[68] Without the ability to strike, a big tool in the mob’s toolkit disappears. This all means that there is even less of a chance that the Mafia can provide extra-legal governance.

Finally, diversity hiring practices are a fact of life in Corporate America and even though the ILA long resisted such efforts, it is slowly being implemented nonetheless.[69] The last real “waterfront racket” the mob still seems to possess is the ability to give sweetheart jobs to their preferred candidates. However, as the union becomes more diverse and hires more women and dock workers from other ethnicities, the mob’s grip will weaken. This can be seen in practice with Newark’s Local 1233. During the UNIRAC days, its local president Carol Gardner was connected to corrupt businessmen and the likes of Tino Fiumara and Michael Coppola.[70] Nowadays, it is deemed a “Black” local as the majority of African American dockworkers are placed there.[71] While that may be done to protect the “good jobs” for “preferred candidates” it also has the effect of diminishing the mob’s influence over it given the lack of potential ethnic solidarity/kinship/family relationship. This can be seen in the fact that this local was not named in either Michael Coppola’s trial or in Depiro’s Christmas shakedown case. With a better-represented membership reflecting the make-up of the surrounding neighborhoods, the last vestiges of the Mafia’s presence will start to slip away.

All that is to say, container terminals are owned by corporations that cannot be intimidated or shaken down and the one ace-in-the-hole (labour unions) that the Mafia processes (or possessed) have structurally declined to reflect the realities of the modern economy.

The weak link in this line of thinking, however, remains Metro or the Metropolitan Marine Maintenance Contractors’ Association. I started to compile company information for each respective member as I did the NYSA, but quickly realized I was getting very little on either CapitalIQ or Google. Some of the websites looked very suspect like they haven’t been updated in years. From the little data I could gather, it was evident that these businesses were privately owned and on the smaller side (<100 employees). The lack of size and corporatism would make them ideal targets for mob infiltration. And indeed, the record does reflect that with both Andrew Gigante’s and Joseph Perez’s involvement with Metro members into the mid-2000s. It also fits the Mafia’s MO to a tee. The mob seems to go down the value chain or geography whenever it is booted from a key market. This has been seen in construction, where investigators noticed in the late 1990s that the Mafia was concentrating on medium-size renovation jobs worth less than $10 million rather than the large commercial and residential projects worth $50 million or more.[72] A similar pattern emerges in waste management following the dismantling of the Mafia’s New York garbage cartel in 1995. An indictment came down in 2013, showcasing the mob’s continued presence in the waste industry, but showed that its operation centred around the edges of New York’s metropolitan area including Rockland and Westchester counties.[73] The same logic can apply here. With an inability to extort container terminal operators or stevedores directly, the Mafia might have moved downstream and started influencing periphery service providers in the port ecosystem. Now I can’t necessarily prove directly that the Mafia is not involved with any Metro members, but there is indirect evidence showcasing that whatever mob presence is there, it can’t be that substantial. To do that, we have to turn our attention back to the ILA-Metro fund.

As discussed previously, the 2000s waterfront indictments largely focused on the Mafia’s attempt to control the various ILA funds, chiefly among them being the Metro-ILA through contracts doled out to mob-associated vendors. Looking at their website, one can see that their benefit and healthcare providers including Aetna, Cigna, and The Hartford among others which are all giant S&P500 publicly traded companies with zero Mafia affiliations. Metro-ILA’s fund manager is Sage Company, a Texas-based asset manager that oversees billions of dollars in AUM. All service providers to Metro-ILA’s funds are large, corporatized entities exhibiting none of the traits of the “fly by night” companies the mob has used in the past to siphon money out of unions. This coupled with management-appointed Metro trustees’ pushback against signing off on Mafia vendors in the early 2000s makes it difficult to believe that the Genovese and Gambino families have any degree of control or influence over Metro members. Thus, even at the weakest link of the armour, one can hardly see a trace of the mob’s presence.

What does this all mean? I’m not saying that there are no crimes being committed at the ports of New York/New Jersey. That is all very likely happening, and mob members and associates are probably responsible for some of it. I’m not saying that the ILA is free of Mafia influence and some locals could very well still be under the unfortunate paws of organized crime. I’m not saying there are no corrupt middle managers at a stevedore or a container terminal operator that allows criminal entities to sneak through drugs and other contraband. That is probably taking place. What I am saying, however, is that waterfront racketeering is not taking place. Neither La Cosa Nostra nor any other organization is providing extra-legal governance services at the port by helping enforce contracts. The mob is too weak for that. The unions are too weak for that. The docks of the 21st century are ruled by private equity and today’s Mafia is no match for them. What are my final thoughts on the Waterfront Commission’s demise? I think Roman Emperor Decius said it best:

“Let no one mourn; the death of one soldier [government agency] is not a great loss to the republic.”

As always shout out to the R/Mafia Discord. Please check out JoePuzzles234’s website on California’s Cosa Nostra and The Black Hand Forum for the most well-researched Mafia information.

Photo credits: Courtesy of Newsday, New York Post and Black Hand Forum, members Eboli, richard_belding, and JoePuzzles234.

[1] James B. Jacobs with Coleen Friel and Robert Radick, “Gotham Unbound: How New York City was Liberated from the Grip of Organized Crime”. 1999. Page 13.

[2] Sergi, A., Reid, A., Storti, L. and Easton, M. “Ports, Crime and Security Governing and Policing Seaports in a Changing World”. 2021. Chapter 1.

[3] Alan A. Block, “Space, Time, and Organized Crime”. 1994. Page 52.

[4] Ibid. Page 53.

[5] Peter Reuter, “Racketeering in Legitimate Industries: A Study in the Economics of Intimidation”. Prepared for the National Institute of Justice (Santa Monica, California, Rand Corporation, October 1987). Page 67.

[6] Alan A. Block, “The Business of Crime: A Documentary Study of Organized Crime in the American Economy”. 2019. Page 181.

[7] Phil Mintz, “Lawyer Indicted In Embezzlement”. Newsday (Suffolk Edition). November 5th, 1987. Page 29.

[8] Peter Reuter, “Racketeering in Legitimate Industries: A Study in the Economics of Intimidation”. Prepared for the National Institute of Justice (Santa Monica, California, Rand Corporation, October 1987). Page 41.

[9] Other factors include the size and sophistication of the industry racketeers seek to dominate, elasticity of demand, market structures, regulatory oversight, political alignment, among others.

[10] U.S. Senate, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Organized Crime: 25 Years After Valachi: Hearing. (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1988). Pages 373-374. Link.

[11] Alan A. Block, “The Business of Crime: A Documentary Study of Organized Crime in the American Economy”. 2019. Chapter 6; Charles R. Babcock, “Dockworkers’ Boss Indicted In Fraud and Racketeering”. The Washington Post. January 18th,1979. Link.; Arnold H. Lubasch, “11 Indicted in Dock Inquiry”. The New York Times. March 7th, 1979. Link.

[12] Ibid.; U.S. v. Local 1804-1, Intern., 812 F. Supp. 1303 (S.D.N.Y. 1993).

[13] United States v. Gotti, et al. No. 02 Cr. 606 (E.D.N.Y.). See an online copy here.

[14] New York State Attorney General, June 4th, 2002, 17 Associates Of The Gambino Organized Crime Family Indicted [Press Release]; Anthony M. DeStefano, “Dish Caught on Tape: Feds make mob shakedown case”. Newsday. December 23rd, 2002. Page A5.

[15] Jim Callaghan & Tom Robbins, “Island in the Schemes”. The Village Voice. June 18th, 2002. Link.

[16] United States v. Gotti, et al. No. 02 Cr. 606 (E.D.N.Y.). See an online copy here; U.S. v. International Longshoremen’s Ass’n, 518 F. Supp. 2d 422 (E.D.N.Y. 2007).

[17] Jim Callaghan & Tom Robbins, “Island in the Schemes”. The Village Voice. June 18th, 2002. Link; John Marzulli, “Pol trashed at Gotti trial: Say he delivered mob cash”. Daily News. January 29th, 2003. Page 21.

[18] U.S. v. International Longshoremen’s Ass’n, 518 F. Supp. 2d 422 (E.D.N.Y. 2007); John Marzulli, “Pol trashed at Gotti trial: Say he delivered mob cash”. Daily News. January 29th, 2003. Page 21.

[19] The Journal of Commerce, “In Trade and Shipping”. The Miami Herald. October 18th, 1994. Page 3B.

[20] U.S. v. International Longshoremen’s Ass’n, 518 F. Supp. 2d 422 (E.D.N.Y. 2007); John Marzulli, “Pol trashed at Gotti trial: Say he delivered mob cash”. Daily News. January 29th, 2003. Page 21.

[21] Anthony M. DeStefano, “S.I. Pol Paid Off Mobsters, DA Says”. Newsday (New York). February 6th, 2003. Page A22.

[22] U.S. v. International Longshoremen’s Ass’n, 518 F. Supp. 2d 422 (E.D.N.Y. 2007); John Marzulli, “Pol trashed at Gotti trial: Say he delivered mob cash”. Daily News. January 29th, 2003. Page 21.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Jim Callaghan & Tom Robbins, “Island in the Schemes”. The Village Voice. June 18th, 2002. Link.

[25] The New York Post described Molfetta as being a one-time driver of Gambino underboss-turned-informant Salvatore “Sammy the Bull” Gravano. See Kati Cornell Smith, “2 Accused of Lying at Gotti Trial”. The New York Post. July 8th, 2004. Link.

[26] U.S. v. International Longshoremen’s Ass’n, 518 F. Supp. 2d 422 (E.D.N.Y. 2007); Link.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Kati Cornell Smith, “2 Accused of Lying at Gotti Trial”. The New York Post. July 8th, 2004. Link.

[29] Anthony M. DeStefano, “Chin to Stick Neck Out For Plea on Robe Ruse”. Newsday (Nassau). April 7th, 2003. Page A14; John Marzulli, “Mob son says he’s out of job”. Daily News. July 6th, 2002. Page 7.

[30] U.S. v. International Longshoremen’s Ass’n, 518 F. Supp. 2d 422 (E.D.N.Y. 2007); Link.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Tom Robbins, “Secrets of the Mob”. The Village Voice. May 8th, 2007. Link.

[34] Jim Callaghan & Tom Robbins, “Island in the Schemes”. The Village Voice. June 18th, 2002. Link.; Tom Robbins, “They Cover the Waterfront”. The Village Voice. February 26th, 2002. Link.

[35] Ibid.

[36] John Marzulli, “Mob son says he’s out of job”. Daily News. July 6th, 2002. Page 7; Jim Callaghan & Tom Robbins, “Island in the Schemes”. The Village Voice. June 18th, 2002. Link; Tom Robbins, “They Cover the Waterfront”. The Village Voice. February 26th, 2002. Link.

[37] United States v. Coppola, 671 F.3d 220 (2d Cir. 2012). Link.

[38] Tom Robbins, “Secrets of the Mob”. The Village Voice. May 8th, 2007. Link.; Tom Robbins, “They Cover the Waterfront”. The Village Voice. February 26th, 2002. Link.

[39] Tom Robbins, “They Cover the Waterfront”. The Village Voice. February 26th, 2002. Link.

[40] U.S. v. International Longshoremen’s Ass’n, 518 F. Supp. 2d 422 (E.D.N.Y. 2007); Link.

[41] A third waterfront case came to my attention after I wrote that section. In March 2002, Genovese associate Nicholas Furina and six other co-conspirators were arrested for extorting dockworkers. Furina alongside ILA officials at Local 1588 used their position to extort kickbacks from longshoremen in exchange for better jobs that carried higher earning potential. Furina also enlisted the help of unnamed management employees at Global Terminal to collect payments from longshoremen at Local 1588. Despite this, there was no allegation of any direction extortion of Global Terminal or their stevedore P&O Ports. See Mitchel Maddux, “7 charged with extorting dockworkers”. The Record. March 8th, 2002. Page A-4.

[42] John Marzulli & Cory Siemaszko, “Rats sink mob ship: Colomobos in cage”. Daily News. January 21st, 2011. Page 19; Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Mafia Takedown: Largest Coordinated Arrest in FBI History”. Press Release. Link.

[43] Federal Bureau of Investigation, “Mafia Takedown: Largest Coordinated Arrest in FBI History”. Press Release. Link.

[44] United States v. Depiro, et al. No. 10 Cr. 851 (D.N.J.). See an online copy of the indictment here; Memorandum of Detention.

[45] United States v. Cicalese, et al. No. 11 Cr. 0027 (E.D.N.Y.) See an online copy of the indictment here.

[46] United States v. Coppola, 671 F.3d 220 (2d Cir. 2012). Link.

[47] George Fiala, “American Stevedoring Gone From Red Hook Terminal”. The Red Hook Star Revue. August 27th, 1994. Link.; American Stevedoring, Inc., Plaintiff V. – International Longshoremen’s Association [2013] Case 1:13- cv- 00918- UA, United States District Court Southern District Of New York. Link.; Rich Calder, “Piers ‘king’: Port Authority, dock union ‘colluded’ against me”. New York Post. September 10th, 2013. Link.

[48] See “Shipped Out: A single industry once dominated Brooklyn’s waterfront. Where did it all go?” for a great article on the history of Brooklyn’s port throughout the centuries. Link.

[49] Benjamin Sutton, “Shipped Out: A single industry once dominated Brooklyn’s waterfront. Where did it all go?”. BKLYNR Issue 7. July 4th, 2013.

[50] Elizabeth Hays, “Keep marine terminal open, says Nadler”. Daily News. July 30th, 2003. Page 33.

[51] Daniel Geiger, “Brooklyn’s last port is clinging to a site coveted by developers”. Crain’s New York Business. January 21st, 2018. Link.

[52] George Fiala, “American Stevedoring Gone From Red Hook Terminal”. The Red Hook Star Revue. August 27th, 1994. Link.

[53] Ibid. Elizabeth Hays, “Keep marine terminal open, says Nadler”. Daily News. July 30th, 2003. Page 33.

[54] Charles V. Bagli, “Lease Ends Uncertainty for Red Hook Cargo Docks”. The New York Times. April 25th, 2008. Link.

[55] American Stevedoring, Inc., Plaintiff V. – International Longshoremen’s Association [2013] Case 1:13- cv- 00918- UA, United States District Court Southern District Of New York. Link.

[56] Ibid.

[57] Ibid.

[58] Tom Hays, “Feds Link N.Y. Man to Organized Crime”. Associated Press. May 26th,2004. Link; John Marzulli, “Authorities to go after mob ‘On The Waterfront’ for the first time in 60 years”. Daily News. August 5th, 2013. Link.

[59] Tom Hays, “Feds Link N.Y. Man to Organized Crime”. Associated Press. May 26th,2004. Link.

[60] George Fiala, “American Stevedoring Gone From Red Hook Terminal”. The Red Hook Star Revue. August 27th, 1994. Link; Eliot Brown, “American Stevedoring Sticking Around Red Hook After All”. Observer. April 24th, 2008. Link.

[61] Shawn Boburg, “Port Authority dock deal probed”. The Record. August 27th, 2014. Link.

[62] Rich Calder, “Piers ‘king’: Port Authority, dock union ‘colluded’ against me”. New York Post. September 10th, 2013. Link; Jamie Schuh, “American Stevedoring Ousted From Red Hook Terminal”. Patch. October 18th, 2011. Link.

[63] Dylan Thomas, “Global private equity dry powder approaches $2 trillion”. S&P Global. December 21st, 2022. Link. For more information about private equity, please read Bain’s annual global private equity reports. Link to their 2023 report can be found here.

[64] Jerry Capeci & Tom Robbins, Mob Boss: The Story of Little Al D’Arco, The Man Who Brought Down The Mafia. 2013. Page 139.

[65] Gary Buiso, “New hook brew – Beer distributor eyes move to nabe”. Brooklyn Paper. November 19th, 2008. Link; Daniel Geiger, “Brooklyn’s last port is clinging to a site coveted by developers”. Crain’s New York Business. January 21st, 2018. Link.

[66] Daniel Geiger, “Brooklyn’s last port is clinging to a site coveted by developers”. Crain’s New York Business. January 21st, 2018. Link.

[67] David Shepardson & Nandita Bose, “Biden signs bill to block U.S. railroad strike”. Reuters. December 2nd, 2022. Link.

[68] Lisa Baertlein, “US West Coast port workers shut some terminals in showdown over pay”. Reuters. June 2nd, 2023. Link.

[69] Ted Sherman, “Agency finally releases long-hidden reports citing mob ties and corruption at NY/NJ ports”. NJ.com. March 23rd, 2021. Link; Patrick McGeehan, “Told to Diversify, Dock Union Offers a Nearly All-White Retort”. The New York Times. November 30th, 2011. Link.

[70] Thomas J. Salerno & Tricia N. Salerno, United States v. Scotto: Progression of a Waterfront Corruption Prosecution from Investigation through Appeal, 57 Notre Dame L. Rev. 364 (1982). Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol57/iss2/6

[71] “Longshoremen’s Association Linked to Lack of Diversity, Crime, and Corruption”. LabourPains. April 1st, 2021. Link.

[72] Selwyn Raab, “Investigators Detail a New Mob Strategy on Building Trades”. The New York Times. August 8th, 1999. Link.

[73] USA v. Carmine Franco, et al. No. 13 cr. 015 (S.D.N.Y.). See an online copy here.